Recently, my wife and I returned from an enriching five-week trip to the Holy Land. During our final days, we spent time with friends in Alon Shvut. After sharing our experiences, they asked, “What was the highlight of your trip?”

My response was immediate: the verse:

עיני ה׳ אלקיך בה מראשית השנה ועד אחרית שנה

“The eyes of Hashem are always upon it, from the beginning of the year to the end of the year”

I didn’t recite this verse lightly; I truly felt it. It was as if a comforting presence had been with us every single day of the trip.

It was a coincidence—or perhaps not—that my mother’s fifth yahrzeit was two weeks after our return from Israel. I hadn’t consciously been thinking about it, especially since my father’s yahrzeit occurred while we were in Israel. We visited his parents’ graves on Har HaMenuchot, but I felt stressed about not being in Melbourne. As is customary, I needed to find a synagogue where I could comfortably receive maftir on Shabbos and serve as chazzan for the yahrzeit, which also fell on Shabbos.

This proved challenging. I wasn’t keen on attending any of the numerous “minyan factories” near our accommodation, nor was I drawn to larger synagogues like Yeshurun in Jerusalem, although I’m sure they would have accommodated me.

By chance, while wandering near Machane Yehuda, I came across a quaint, albeit somewhat dilapidated, synagogue. It wasn’t Eidot HaMizrach, and they followed Ashkenazi traditions, which was close enough to the Nusach Sefard I’m accustomed to. Their Shabbos service started at 8 a.m., perfect for me.

While I might have been concerned about commemorating my father’s yahrzeit, it was my mother’s “presence” in Israel that was astounding and pervasive.

Family Roots

My mother’s parents came from two towns near Brisk (Brest-Litovsk): Terespol and Kodeń.

Before World War II, Terespol had a Jewish population of approximately 1,000–1,500, a significant portion of the town’s residents. The community had synagogues, schools, and actively participated in local trade and crafts. Terespol is just 3–5 kilometers from Brisk, separated by the Bug River, which now forms the border between Poland and Belarus. A bridge connects the two towns, making them essentially neighbors.

Kodeń, a nearby village, also had a Jewish community before the war, though smaller, estimated at a few hundred Jews.

My maternal grandparents were married in Brisk before moving to Warsaw, where my mother was born.

Unexpected Connections

The sense of connection deepened on the Friday night before our departure from Melbourne. During synagogue announcements, the gabbai mentioned various simchas. The last was an engagement between a family from São Paulo, Brazil, and a family from Melbourne. The bride’s father, whose surname was Flaksberg, was present.

I remembered my mother mentioning a cousin from Brazil named Shmiel Leib Flaksberg, though they hadn’t been in contact for over 40 years. I approached the bride’s father and asked if he was related to Shmiel Leib. He looked at me, astonished, and replied that Shmiel Leib was his grandfather.

When I explained that we were related, we were both stunned.

After World War II, my mother’s parents immigrated to the nascent State of Israel and established a small dairy farm in Yafo, Tel Aviv. My mother completed her schooling in Israel and spoke fluent Hebrew. Shmiel Leib and his family were frequent visitors to the farm. He even assisted my grandparents in transferring funds to Australia when they emigrated in the late 1950s.

I later discovered that Shmiel Leib’s son, Marek (Meir), now lives in Ra’anana. I got his contact information and reached out. Marek was visiting Jerusalem with his grandson, so we arranged to meet for coffee at Mamilla Mall.

Although Marek vividly remembered accompanying his father on Motzei Shabbos trips to my grandparents’ farm—apparently to purchase cows for Shechita and later sale—he wasn’t sure how we were related. Like many in his generation, he hadn’t spoken much with his father about family connections.

I’m now trying to piece that puzzle together. A possible clue is that his family hailed from Sławatycze, a nearby town with many people sharing my grandfather’s surname.

The Gershenzon Connection

My grandmother’s maiden name was Gershenzon. The family had a presence in nearby Brisk and are, unsurprisingly, Leviim — Mishpachas HaGershuni. About 15 years ago, I discovered a Gershensohn cousin named Rachel in Ra’anana, though when her family emigrated to the USA, their name became “Samson.” I’ve been in touch with Rachel over the years. I had met one brother, Hershel. During this trip, I learned that her brother Lee was visiting from LA and her sister Shari was now in Jerusalem. I hadn’t met Shari or Lee before.

Shari lived in Kiryat Shemone. Her husband, Rav Tzefania Drori, was the Chief Rabbi of Kiryat Shmona and the rosh yeshiva of the Kiryat Shmona Hesder Yeshiva from 1977. Kiryat Shmona has been devastated during the current war with Hezbollah1.

Lee Samson is a very well known business man and philanthropist in LA. He is a member of the International Board of Trustees of the Simon Wiesenthal Center and serves on the Board of Governors of Cedars Sinai Medical Center and the Board of Directors of the Orthodox Union2.

We shared a lovely lunch at the King David, and I had a warm feeling connecting with members of my mother’s family.

The Legacy of Elka

My mother’s name was Elka. Baruch Hashem, in the wider family, we now have four little girls named Elka and a boy named Elkana. Unsurprisingly, there were many Elkas in the Gershensohn family tree. One of these was a cousin of my mother’s named Elka Lowenstein, although she was known as “Ella.” (It wasn’t uncommon for secular Zionists to suggest that names like Elka were Yiddish and passé—my mother became known as Elisheva in school, and Elka Lowenstein became Ella.)

For about seven years, the Lowensteins moved from Israel to Melbourne, Australia, because they had been promised that “there was money growing on the trees.” They lived in Elizabeth Street in Ripponlea, and we used to pick up Ella and her two daughters, Tzippi and Rinat, each morning to take them to school (Beth Rivkah, where Ella worked in the kindergarten). The Lowensteins moved back to Israel, and though we shared many memorable years, including joint holidays and excursions, we lost touch. I hadn’t seen Tzippi or Rinat in over 40 years. I reached out to them, and to our great excitement, my wife and I took two trains to Kiryat Motzkin to meet them and Ella’s sister Rachel. We shared a very warm day reminiscing and committing to filling in some gaps in the family tree.

Ella was also related to the Bigon family (also spelled Begin). My mother had often spoken about Rav Dov Begun and his brother. They, too, were frequent visitors to my grandparents’ farm in Yafo. I had visited HaRav Begon on previous visits, and one of my sons spent the summer break in his Yeshivah.

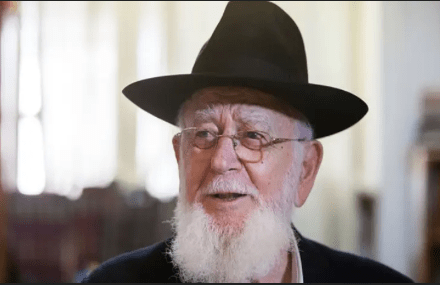

Rav Dov Begon was educated in the secular kibbutz movement yet was drawn to explore his Jewish heritage. His journey led him to Merkaz HaRav Kook Yeshiva in Jerusalem, where he studied for ten years, becoming one of the foremost students of Rabbi Zvi Yehuda Kook3. During the Six-Day War, HaRav served as a commander in the Israeli Defence Forces and participated in the liberation of Jerusalem. He forged a new path in the field of kiruv (outreach) and teshuva (repentance), helping Jews of all backgrounds reconnect with their heritage, uniquely based in the Religious Zionist community in Israel.

Connections in Shiloh

We spent a day in Shiloh, part of which was at the wonderful Gva’ot winery, where we enjoyed eight delectable wines paired with excellent cheese. Looking at the signage, I was again struck by the name “Drori”—another connection to my mother’s family. Gvaot is a boutique, family winery founded in 2005 by entrepreneur Amnon Weiss and Chief Winemaker Prof. Shivi Drori, an agronomist and researcher in viticulture and oenology at Ariel University. A research study led by Prof. Drori revealed approximately 60 ancient varieties of wine grapes from the Land of Israel in general, and Samaria in particular, from which wines have been produced for thousands of years. Shivi is a son of Sharri and Rav Tzefania Drori.

By now, I felt completely enveloped. Would a day pass without another gentle cosmic nudge from my mother?

As we were about to leave Shiloh, our friend suggested I pray Mincha in the main synagogue, architected to resemble parts of the Mishkan (which had been in Shiloh). At the end of prayer, a member of my wife’s family who lives in Shiloh suggested I meet the new Rabbi of Shiloh, Rabbi Yehonadav Drori, who had replaced Rabbi Elchanan Bin Nun after his 30-year tenure. Again, a family connection through my mother. I introduced myself and mentioned that we were family. We exchanged emails, and I will send him a family tree link.

Acts of Chesed

My mother was always involved in acts of Chesed (kindness). She had spent her formative school years in Israel but never forgot her closest friends. One of these was her lifelong friend Chava, who lives in a modest flat in Bat Yam. My mother wrote to Chava regularly, sending her clothes, money, and gifts for her family. They had a wonderful bond, and their love for each other was always palpable whenever they spoke on the phone.

Every trip I took to Israel included a visit to Chava. On this trip, our visit was towards the end. As we sat in her flat, especially after all the previous events, I wondered whether I was visiting her or visiting her on behalf of my mother! Was I a Shaliach (messenger) during this trip?

The Concept of Shlichus

The Gemara in the second chapter of Kiddushin asks what the source of the concept of Shlichus is. How do we know that one person can substitute for another according to the Halacha?

In respect of a Get, the Torah uses the root (Devarim 24) “v’shalach” which implies that a Get can be sent (by an appointee). Regarding the separation of Teruma from Chulin, the Torah states (Bamidbar 18) “ken tarimu gam atem,” and from the words “gam atem” we derive that someone else can separate Teruma on one’s behalf. We can conclude that from these verses there is authorisation to appoint someone to perform an act or mitzvah on one’s behalf.

At the same time, we have a concept that a Shaliach doesn’t just perform a transaction on behalf of the sender, but it is as if the Shaliach is the sender. That is, “shelucho shel adam k’moso” (one’s messenger is like oneself). The Gemara learns this from the Korban Pesach. Each person is enjoined to slaughter a Korban Pesach. Yet, we find that one person does so for a group of people. How can that be, given that each person needs to perform Shechita?

“Rabbi Yehoshua ben Korcha said: How do we know that one’s messenger is like oneself? As it says, ‘The entire assembly of the congregation of Israel shall slaughter it toward evening’ (Exodus 12:6). Does the entire congregation slaughter? Surely only one person slaughters! From here we learn that one’s messenger is like oneself” (Kiddushin 41b).

The Gemara learns from here that the Shaliach not only effects an act of Shechita but, in addition, it is considered as if the very person who appointed the Shaliach did the Shechita. That is, it is “mamash k’moso” (truly like oneself).

Are there in fact two perspectives through which Shelichus is viewed by the Torah? This question has occupied many Acharonim, ranging from Rabbi Shimon Shkop, Rabbi Chaim Brisker, and Rabbi Itzele Volozhiner as cited by Rabbi Baruch Ber, the Rogachover Gaon as cited by Rabbi Menachem Mendel Kasher, the Ohr Sameach, Rabbi Yosef Engel and more.

I’m not intending here to present their somewhat similar approaches to explaining the phenomenon. Rather, for the purposes of this essay, we can explain that when an act that is being performed causes some transactional change, then the Shaliach is acting with the authority and on behalf of the sender. We do not assume, however, that the Shaliach is “like” the sender in all cases.

For example, a Kohen cannot ask a Yisrael to perform the Avodah in the Beis HaMikdash by stating that the Yisrael assumes “the body” of the Kohen. In such a case, where the Shaliach’s action isn’t valid as an act in itself, the terms of the Shlichus do not even begin, and it is an invalid Shelichus.

On the other hand, a man can appoint a Shaliach to divorce his wife. We might think that this also makes no sense since the Shaliach isn’t married to the woman, so what is the meaning of the Get? In essence, though, there is nothing preventing a man from giving a Get (unlike a Yisrael doing the Avodah). Therefore, a Shaliach can be appointed in such a case.

This leads us to an interesting case where a man appoints a Shaliach to divorce his wife. This is valid because men have the ability in general to divorce a woman. But what happens if, after sending the Shaliach and before the Get took place, the sender suffered a mental breakdown and was no longer compos mentis?

If we say that the Shaliach is the embodiment of the sender, then the Shaliach ought to be considered mentally affected and unable to complete the Shlichus (the Ohr Sameach explains that this is the view of the Tur in Even HaEzer 128). On the other hand, if he is acting on behalf of the sender and the sender was perfectly normal and cognisant at the time of appointment, then the transaction could take place, at least on a Torah level (the Ohr Sameach contends that this is the view of the Rambam, Gerushin 2:15).

These considerations occupied my mind when I wondered about the nature of my interactions in Israel. When, for example, I was visiting my mother’s friend, I was doing a mitzvah, but was it as if I was the embodiment of my mother at that time in the sense of “Shelucho Shel Adam K’moso,” or was it a regular style Shelichus where I was performing the act on behalf of my mother?

Though, as I have outlined above, I had felt cosmically that my mother was hovering around all the interactions, given that she had passed away and was in a higher abode, perhaps the way to understand it was that she had passed on life tasks which, though they were on her behalf when she was alive, now assumed a continued valid Shelichus (also) on her behalf even after she has left this world.

The lesson to me is clear. Parents impart values and heritage. Some overtly tell their children what they ought to do. Other parents are less overt but achieve the same effect through their actions and personal example. I recognise that in our day and age, parenting has assumed a less overtly prescriptive approach, but even in my time, I feel less that I was told to do something and more that I sensed this was the right thing to do, and it was therefore my duty to do so.

On this day, my mother’s 5th yahrzeit, I feel the imperative of emulating her values and passing these onto my own children and grandchildren as acutely as I did when she was in this world and I was younger. When children are able to follow their parents’ upright morals and ethics, then though it is perhaps no longer “mamash k’moso” in the physical sense, the original Shlichus continues and works through the prism of a momentum that we often call the Mesorah.

May the Neshama of אמי מורתי Elka bas Tzvi עליה השלום have an Aliya

Footnotes

- Rav Drori also headed the Aguda LeHitnadvut and served as Av Beit Din of the northern conversion court. Rav Drori is considered a leading scholar of the Religious Zionist movement. He first studied at the Bnei Akiva Kfar HaRoeh high school yeshiva when Rabbi Moshe-Zvi Neria served as rosh yeshiva. Later, he helped establish Yeshivat Kerem B’Yavneh and then studied at Mercaz haRav yeshiva. Ironically, Yeshivat Kerem B’Yavneh was my alma mater, though I didn’t know of Rav Drori’s connection. He became an important student of Rabbi Zvi Yehuda Kook. ↩︎

- He is Chairman of the Board of Young Israel of North Beverly Hills, and he recently dedicated the Samson Center at Yeshiva University of Los Angeles High School. Additionally, he serves on the Los Angeles Philharmonic Board of Trustees. His philanthropy also centers on many institutions in Israel, including NCSY’s Anne Samson Jerusalem Journey, Shaare Zedek Hospital’s Lee and Anne Samson Interventional Neuro‐Radiology Unit in Jerusalem, The Museum of Tolerance Jerusalem, The Samson Family Wine Research Center at Ariel University, and more. ↩︎

- During the Six-Day War, HaRav served as a commander in the Israeli Defence Forces and participated in the liberation of Jerusalem. He forged a new path in the field of kiruv (outreach) and teshuva (repentance), helping Jews of all backgrounds reconnect with their heritage, uniquely based in the Religious Zionist community in Israel. ↩︎

You must be logged in to post a comment.