The month of Shevat is, for me, perennially a difficult one. My father, alav ha-shalom, has his yahrzeit on the 3rd, and my mother, aleha ha-shalom, has hers in the coming week on the 29th. I am sure there is nothing unique about feeling somewhat alone in their absence.

Barukh Hashem, my father has seven great-grandchildren who carry his name, as does my mother. Perhaps obsessively, even when their English names vary slightly, I insist on calling them all by their Jewish names. It can be confusing with my own grandchildren: when I say “Shaul Zelig,” three boys turn to me.

My mother’s name was Elka, which is a little easier, because the girls often have a middle name, so I can distinguish between Elka X and Elka Y. There is probably a minor thesis in this for anyone inclined to psychoanalyse my obsession, but in simple terms, I take comfort—indeed, I luxuriate—in being able to say their names every day.

Though time moves forward in its measured, ever-changing way, I find that certain constants remain firmly anchored throughout that continuum. Subconsciously, I feel that, where possible, I seek to emulate their values and the way they approached life.

It may be seen as an obsession, as might my tendency towards melancholy when a special occasion—a simcha—takes place. That is simply who I am. I do not apologise for it, and I do not regret these tendencies for a moment.

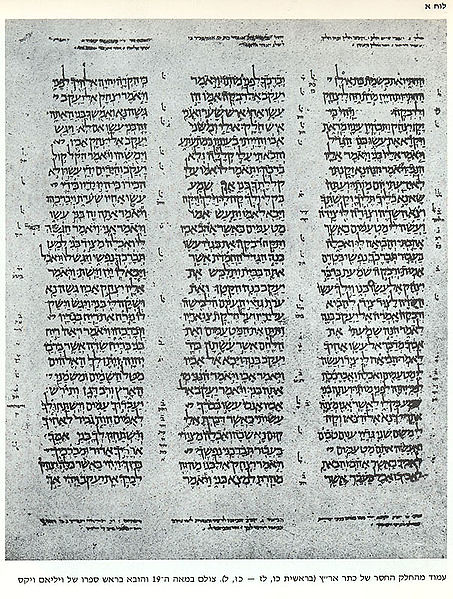

To honour their memory, I have written an essay—quite a long one—on the topic of Birkas Kohanim. After reviewing various parameters of this mitzvah, I delve into the question of Birkas Kohanim outside the context of shul and formal davening.

The essay is too lengthy for a blog post, so I will attach it here as a PDF, which can be printed. It is certainly not the final word on the subject, and I would greatly value any comments, corrections, or feedback. If you know Kohanim who may be interested in this topic and who don’t subscribe to my blog, please feel free to send them a link to this post.

I will borrow a paragraph from the essay as a way of introducing what first piqued my interest..

One impetus for composing this essay stems from personal experience at a Pidyon HaBen ceremony. Following the conclusion, the officiating Rabbi—who was also the Kohen that performed the redemption—invited any other Kohanim present to join in bestowing Birkas Kohanim upon the infant. There were two Kohanim present: the Rabbi and me. As we recited the pesukim of Birkas Kohanim, I observed that the Rabbi raised both his hands over the head of the baby, while I, following my customary practice in such informal contexts, extended only one hand. This practice was consistent with how I have traditionally conducted such berakhos outside of the formal dukhening that occurs during Musaf on Yom Tov in the Diaspora or daily in Eretz Yisrael.

Afterwards, I inquired why he had chosen to use both hands. He responded that while he was unsure of the halakhic reasoning, he was simply following the custom of his father, who was a respected Posek. In contrast, my own practice—what might be termed “halakhic intuition”—led me to use a single hand. Although I could not recall the exact source or rationale at that moment, I had evidently internalised a precedent or explanation that once guided this choice. This essay, then, charts a journey leading to that choice.